If you lived in a village with only one mode of transport, say, a single car per family, then there would be resources that take longer to get at then others. On a computer, the same is true, where the village is the CPU, and the resources are things where data lives or is communicated over, such as a disk drive or a network socket. Things in your own home are quick to fetch; these would be the registers of a CPU. Some things are still quick for you to fetch but you don't keep directly inside your home. Perhaps you have a few of these sheds so you can fit various things, like your garage and a work shed. When the shed and garage don't suffice and you need new supplies, you travel to the store to purchase supplies, bringing them home with you to put in the shed or garage or whatever outdoor storage you own.

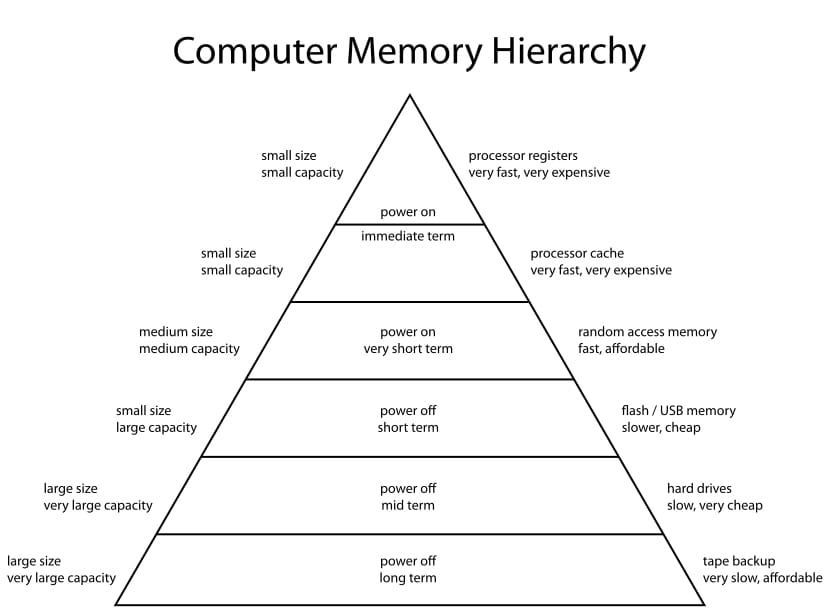

All of this indirectly describes a computer memory hierarchy and the idea behind the hierarchy is that things at the top are generally faster to access while things on the bottom are slow. For some reason it's always drawn like a food pyramid.

As noted, memory hierarchies aren't just about storage of data. The network, for example, is a part of the memory hierarchy of a computer, and is usually below storage, but that doesn't mean that talking over a really fast network interface is going to be slower than accessing a spinning disk drive because the pyramid told us so. It simply means that we can reason about the relative performance of things with reasonable educated guesses. The place for profiling and collecting numbers is not ousted by the existence of the memory hierarchy model. My favorite form of a memory hierarchy is the "Latency Numbers Every Programmer Should Know" collection and there's this neat visual aid that has a time slider so you can compare times across relevant years.

If things are far away, it makes sense to bring them closer, but does this always make sense? Time spent shuttling things from some far off place to our homes makes sense, but what if we are just going to bring something home and never look at it again?

Caches are generally designed the way they are based on two core ideas called temporal locality and spatial locality. Sometimes these ideas are grouped into the notion of locality of reference or just locality. Temporal locality refers to the high likelihood that if you bring something closer for use, you are likely to use it again. Spatial locality refers to the high likelihood that if you bring something closer to you for use, you are likely to want adjacent things to that resource.

Specifically with CPUs, caching layers are designed to benefit data that is repeatedly accessed as well as bringing data in by whole cache lines such that neighboring values are accessible, thereby favoring contiguous data in memory. Structuring data that favors these qualities of locality is often called being cache friendly. If you have a tight loop over an array and wonder why it's so fast, this is why; depending on the size of the array, you are probably going to bring in large chunks of the array for access and if your program access the array multiple times without touching too much unrelated data, you're likely to get a very high cache hit rate. You can actually inspect the rate by which you are hitting or missing the lookup for a particular value in a cache level by running perf over your program. For example, on linux you can run:

$ # allow perf to do it's sampling.

$ echo -1 | sudo tee /proc/sys/kernel/perf_event_paranoid

$ # -d for detailed.

$ perf stat -d program

Performance counter stats for 'program':

117,416.25 msec task-clock # 1.858 CPUs utilized

59,648 context-switches # 0.508 K/sec

3,324 cpu-migrations # 0.028 K/sec

1,875,173 page-faults # 0.016 M/sec

406,889,422,900 cycles # 3.465 GHz (37.34%)

418,921,344,585 instructions # 1.03 insn per cycle (37.40%)

73,495,121,565 branches # 625.937 M/sec (37.51%)

1,542,783,222 branch-misses # 2.10% of all branches (37.56%)

122,094,600,307 L1-dcache-loads # 1039.844 M/sec (37.69%)

4,173,542,186 L1-dcache-load-misses # 3.42% of all L1-dcache hits (37.62%)

1,041,448,237 LLC-loads # 8.870 M/sec (37.55%)

308,710,304 LLC-load-misses # 29.64% of all LL-cache hits (37.33%)

63.190530678 seconds time elapsed

75.387109000 seconds user

4.203457000 seconds sys

$ # or more precisely with exact events chosen

$ perf stat -e L1-dcache-loads,L1-dcache-load-misses,LLC-loads,LLC-load-misses,LLC-stores,LLC-store-misses,LLC-prefetch-misses,cache-references,cache-misses program

Performance counter stats for 'program':

62,785,291,592 L1-dcache-loads (37.44%)

58,672,227 L1-dcache-load-misses # 0.09% of all L1-dcache hits (37.46%)

9,445,705 LLC-loads (37.47%)

1,859,151 LLC-load-misses # 19.68% of all LL-cache hits (37.42%)

10,586,766 LLC-stores (25.05%)

2,284,173 LLC-store-misses (25.14%)

<not supported> LLC-prefetch-misses

164,972,297 cache-references (37.64%)

29,366,970 cache-misses # 17.801 % of all cache refs (37.48%)

35.113199020 seconds time elapsed

34.627643000 seconds user

0.071941000 seconds sys

Where program is the program you want to examine. The events in the middle column we care about start with a capital L; L1 is the first, fastest level cache to the CPU, and LLC stands for Last Level Cache. For L1 it's a dcache for data cache because instructions can also be cached. If we wanted information on the instruction cache we could also request that with icache instead of dcache.

Check out how LLC-prefetch-misses is unsupported on the CPU I am running this example on; sometimes perf events aren't available on all machines and kernel configurations. Lastly, notice how I chucked in cache-references and cache-misses which we can learn the meaning of by going to the man page for man perf_event_open. Here's a snippet from what mine mentions about the two (link to online reference for those who want to follow along and don't have a computer handy):

<snip>

PERF_COUNT_HW_CACHE_REFERENCES

Cache accesses. Usually this indicates Last Level Cache accesses but this may vary depending on your CPU. This may in‐

clude prefetches and coherency messages; again this depends on the design of your CPU.

PERF_COUNT_HW_CACHE_MISSES

Cache misses. Usually this indicates Last Level Cache misses; this is intended to be used in conjunction with the

PERF_COUNT_HW_CACHE_REFERENCES event to calculate cache miss rates.

<snip>

If you want to know more events available to you, you can call perf list. If you are looking for something really specific, sometimes developer guides for CPUs will contain information about event numbers for specific hardware events that you can pass to perf to record.

Bringing things closer is part of a larger principle of being lazy and laziness has performance benefits. Often performance tuning is an odd mix between both doing as little work as possible and being as slim as possible but also utilizing resources to their maximum. ****If you can get away with collecting supplies once a week it is going to be more efficient than going to the store every day. If you can work on data repeatedly that's all next to one-another, you are going to avoid paying for the cost of accessing main memory repeatedly. If you can store data off a disk that doesn't change into an in-memory data structure acting as a cache, you will avoid paying the cost of trapping into the kernel to run a system call for the various reads only the one time you read the file.

To recap:

- We can make educated guesses about the relative performance of how fast it will take to reach data based on a mental model of a memory hierarchy and some averages we can keep in our back pocket. You'll likely build up a sensibility for these numbers over time.

- Caching data is the act of bringing data closer to where the work is happening. Effective caching takes advantage of two types of locality of reference, spatial and temporal, given the high probability that you will want to access something you've used before and the fact that you probably also want to work on adjacent datal. Designing your use of data around this concept is called being cache friendly.

- You can use

perfto collect actual hardware samples on linux. Similar solutions exist for other operating systems. This data gives you a rough gauge of whether or caching is being fully utilized in your program under examination. - Caching is a part of the performance principle of being lazy. If you have to do work, do as little of it as possible.