Once upon a time I studied photography at an art school. It was there that I learned the importance of separation between tones in an image. If the separation, tone or color, between objects in my images wasn't quite right I'd have to redo all my work in order to get a grade. Separation is how we often define our mental maps of the world. For this article, I'll call anything that is distinct from other things an "entity".

Entities have edges. They may have eddies of communication or arrows of connection through these edges. Edges may be incidental, e.g. defined by people you don't know or from natural consequences, or they may be intentional, i.e. the result of deliberate planning and execution. Entities have non-zero surface area, otherwise they wouldn't exist, but that doesn't mean they cannot be relatively invisible.

Clarifying (edges) means simpler mental maps. Simpler mental maps means easier to reason about systems and programs. Simpler systems and programs means increased velocity for progress and experimentation. Each of these examples could be their own posts, but for now it suffices to say that examples of this type of organization (clarification) are,

-

Serialization to the wire (network), disk, and internal datatype definitions individually go into their respective modules

-

Core logic that performs calculations versus reading from disk, e.g. application level versus storage engine logic, are separated

-

Munging layers, or what some call an adapter, that transform data to the shape you so desire are not tied into (1). This is bidirectional; it's equally fair to have the adapting layer work on outbound and inbound interfaces.

Most of this might feel a bit obvious: things have edges and that's how we tell they are distinct, but how does this relate to coding?

It's common to think that programming has to be a balancing act between progress (by accepting breakage) and stability (by leaving things alone). I've talked a bit before about how vital constant experimentation is, but this balancing act is not the only way to go about things. Yes, things break when they have production data running through their digital veins and having instrumentation to gain visibility into your running code in production is crucial to combat this statistic of failure, but let's consider another approach to the development side of correctness.

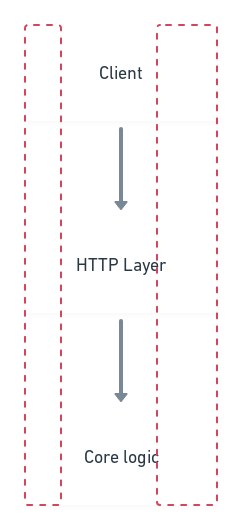

Although it may seem strange for me to use the term artificial when all the boundaries discussed here seem planned by ourselves or by others, I use the term "curtain" here to denote artificial delineations we establish to avoid working in slices. A sliced approach to development means we attempt to get all working functionality, from front to back, one slice at a time. In the following diagram the red boxes are slices of features whereas non-sliced functionality is stable:

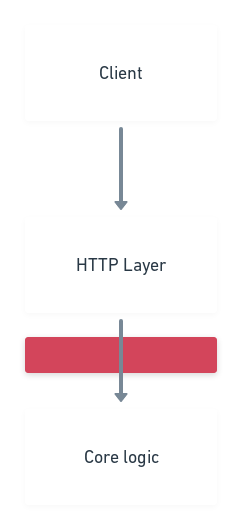

We can define "curtains" (again: artificial edges for the purposes of development) to retain stability in all areas "exterior" to the curtain. "Exterior" may very well be "interior" code! Setting up curtains can be done with feature-flags, parallel implementations or even creating new surfaces where interaction will be performed and migrating after the fact when everything seems settled. As long as the "exterior" to the curtain go on its life as if nothing is wrong, a curtain serves its purpose. Per the example above it might look like this:

In this diagram, you could be setting up the curtain to keep the core of the application stable or the client and interfaces the client talks to stable. A curtain based approach by no means requires having a layered architecture or thinking in that manner. The fact that a curtain is malleable and artificial means we can define its boundaries, but a curtain becomes a slice when it overlaps too many real edges in a system. Why is this any better than a sliced approach?

Curtains buy you breathing room.

There is always an implicit countdown when you keep things stable but don't make progress. "Where is the business value they are adding?" squawks the manager. If you are making a lot of progress but breaking things the countdown timer is time to completion but in the face of churn, top-down pressure, peer-pressure, and so on. Breathing room gives you space to think. Space to think means you can buy yourself breathing room. This helps build healthy systems with reduced complexity and healthy systems means higher rates of progress and experimentation.